|

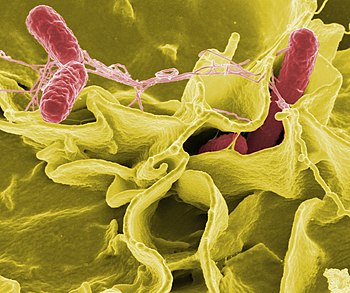

| Color-enhanced scanning electron micrograph showing Salmonella typhimurium (red) invading cultured human cells (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

With the recent recalls of millions of liters of ice cream as well as several tons of hummus, pine nuts, frozen vegetables and various meat products, you might think the American food supply is an unholy mess. It’s not. It’s arguably the safest in the world.

Yet despite continually improving processing methods and quality controls, the number of cases of food-borne illness has remained high since the 1990s, with the incidence of people getting sick from some pathogens increasing.

Some experts wonder if we’ve reached a point of diminishing returns in food safety-whether our food could perhaps be too clean.

Industrial food sanitation practices – along with home cooks’ antibacterial veggie washes, chlorine bleach kitchen cleaners and sterilization cycle dishwashers – kill off so-called good bacteria naturally found in foods that bolster our health. Moreover, eliminating bad or pathogenic bacteria means we may not be exposed to the small doses that could inoculate us against intestinal crises.

“No one is saying you need to eat a peck of dirt before you die to be healthy,” said Jeffrey T. Le Jeune, a professor and head of the food animal research program at Ohio State University in Wooster. “But there is a line somewhere when it comes to cleanliness. We just don’t know where it is.”

The theory that there might be such a thing as “too clean” food stems from the hygiene hypothesis, which has been gaining traction over the last decade. It holds that our modern germaphobic ways may be making us sick by harming our microbiome, which is the system made up of all the microbes-bacteria, viruses, fungi, mites-that live in and on human bodies.

A result of a diminished microbiome is an immune system that gets bored, spoiling for a fight and apt to react to harmless substances ad even attack the body’s own tissues. This could explain the increasing incidence of allergies and autoimmune disorders such as asthma, rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease.

There is also the suggestion that a diminished microbiome disrupts hormones that regulate hunger, which can cause obesity.

When it comes to food-borne illness, the idea is that fewer good bacteria in your gut means there is less competition to prevent colonization of the bad microbes, leading to more frequent and severe bouts of illness. Moreover, an underutilized immune system may lose its ability to discriminate between friend and foe, so it may marshal its defenses inappropriately (against gluten, for example) or not at all.

Animal experiments have lent some credence to the theory. Researchers at Texas Tech University in Lubbock have found that guinea pigs fed less virulent strains of listeria are less likely to get sick or die when later fed a more pathogenic strain. And anyone who has visited a country with less than rigorous sanitation knows the locals don’t get sick from foods that can cause tourists days of toilet-bound torment.

“We have these tantalizing bits of evidence that to my mind provide pretty good support for the hygiene hypothesis, in terms of food-borne illness,” said Guy Loneragan, a professor of food safety and public health at Texas Tech.

This is not to say we’d be better off if chicken producers eased up on the salmonella inspections, we ate recalled ice cream sandwiches and didn’t rinse our produce. But it raises questions about whether it might be advisable to eradicate microbes more selectively.

Taken from TODAY Saturday Edition, The New York Times International Weekly, May 23, 2015