|

| English: (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

ALEXANDRIA, New Hampshire – For most of his life, Kevin Ramsey has lived with epileptic seizures that drugs cannot control.

At least once a month, he would collapse, unconscious and shaking violently, sometimes injuring himself. Nighttime seizures left him exhausted at dawn, his tongue a bloody mess. After episodes at work, he struggled to stay employed. Driving became too risky. At 28, he sold his truck and moved into his mother’s spare bedroom.

Cases of intractable epilepsy rarely have happy endings, but today Mr. Ramsey is seizure-free. A novel battery-powered device implanted in his skull, its wires threaded into his brain, tracks its electrical activity and quells impending seizures. At night, he holds a sort of wand to his head and downloads brain data from the device to a laptop for his doctors to review.

I’m still having seizures on the inside, but my stimulator is stopping all of them,” said Mr. Ramsey, 36, whose hands shake because of one of the three anti-seizure drugs he still must take. “I can go to the store on my own, and get my groceries. Before, I wouldn’t have been able to drive.”

Approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration, the device called the RNS System aims to improve the lives of those whose epilepsy cannot be treated with drugs or brain surgery.

About 110 epilepsy centers have filed paperwork to be able to offer it, said Dr. Martha J. Morrell of NeuroPace, based in Mountain View, California.

Unfortunately, many patients are not referred to these centers by their doctors until they have spent years, even decades, grappling with their condition.

Dr. David M. Labiner, the president of the National Association of Epilepsy Centers, said the “lag time” between diagnosis and referral to a comprehensive center “is still up to 20 years.” Another hurdle: The RNS costs up to $40,000, a figure that doesn’t include $ 10,000 to $20,000 for the surgery, or diagnostic testing. The device also requires a battery change every two to three years.

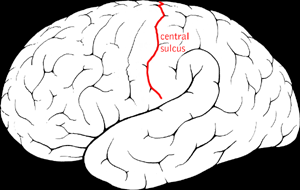

An estimated 2.3 million American adults have epilepsy, and in a third of them, seizures are not controlled by drugs. Brain surgery can relieve seizures completely, but many patients are not candidates because their seizures start in parts of the brain that can’t be removed, such as those needed for language or memory.

Without treatment options, people with intractable epilepsy often find it difficult to hold jobs or to find spouses. They can suffer repeated injuries from falls and burns; their mortality rate is two to three times higher than that of the general population.

“There are people out there who are just desperate for the next treatment,” said Janice Buelow of the Epilepsy Foundation.

In a clinical trial of 191 people at 32 sites, patients received stimulators but did not know whether they were activated. Those with stimulators activated reported a 38 percent reduction in seizures over three months, compared with a 17 percent decrease among those whose stimulators were not, according to the results published in Neurology.

Implantation surgery requires two days in the hospital.

Before the RNS is turned on, a patient’s seizure patterns must be detected, a process that takes months. Then comes a period of trial and error, when the intensity of stimulation is increased or decreased, or the number of pulses altered, to see if the patient experiences fewer seizures.

Mr. Ramsey’s treatment has been more successful than most. Soon after his stimulator was turned on, his major convulsive seizures stopped. But it took three years of adjustments to stop another kind of seizure that resulted in his simply staring.

Mr. Ramsey, who lives on his own, still has cognitive issues. “I forget people’s names all the time,” he said.

Now he is hoping for another life-changing result: “Finding a really nice girl,” he said. “I would like to have a baby so I can raise a family.”

Taken from TODAY Saturday Edition, April 26, 2014